Letterdepressed

This article was originally published in issue 5 of The Magazine, published December 6, 2012 by Marco Arment; edited by Glenn Fleishman.

Loren Brichter’s Letterpress is a beautifully designed iOS game that mixes Scrabble with the ancient Japanese strategy game Go. It’s the best casual game I’ve played in years, and it’s wasted more of my time than I’ll admit.

The trouble is, as the executive editor of this publication can attest, figuring out an ideal strategy isn’t obvious. A lot of otherwise brilliant players seem to struggle at Letterpress. [Editor’s note: I have no idea what you’re talking about.-gf]

This may come from players being stuck in a Scrabble mentality. In Scrabble, the game requires opponents start in the middle and work to the edges. Oddball letters like Z and Q have the highest values, and thus are desirable to preserve and place carefully.

In Letterpress, the worth of a letter isn’t determined by how difficult it is to use, but its position. Scrabble players start in the middle, but the savvy Letterpress player starts in the corners. The objective of Scrabble is to construct words, while the point of Letterpress is to prevent your opponent from doing so.

The basics

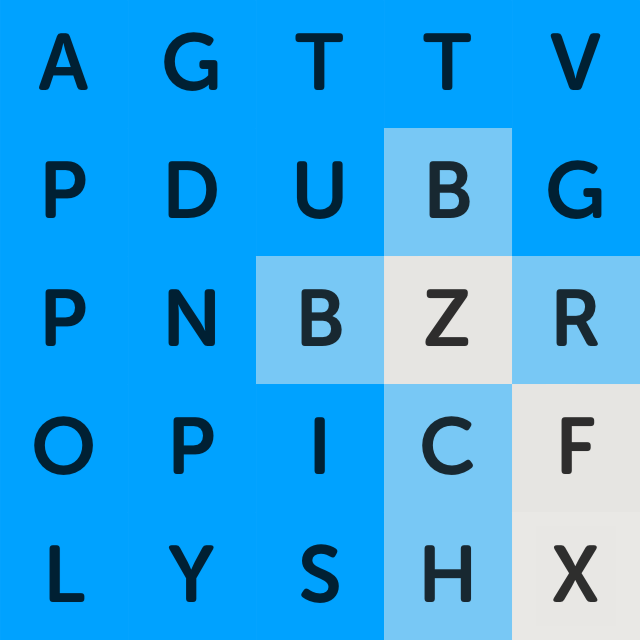

Two players see the same five-by-five grid of letters. The game proceeds in turns in which legitimate words must be played (according to the built-in dictionary), or a player must pass. Each word you create may be used only once, may not be a prefix of a previously played word (but can end in the same letters), and must be at least two letters long.

The board's starting position

Tapping letters on the board puts them in a row below the player avatars and scores, and above the board. Drag letters to rearrange them, or tap to return them to their position on the board. You can test words even when it’s not your turn.

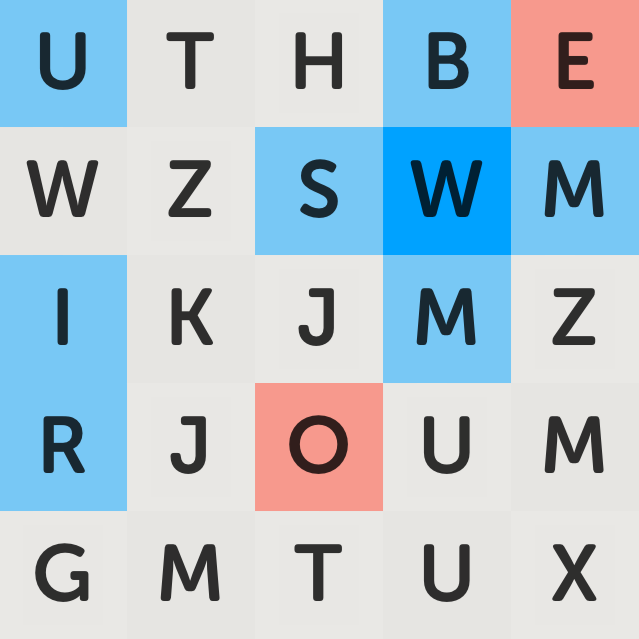

Playing a word stakes a claim on the letter tiles that comprise it. Letterpress shows that tiles are claimed by changing the color, in the default color scheme, to blue (for the local player) or red (for the remote opponent).

A tile’s background is a light shade of the color unless it is surrounded on all sides on the board by tiles claimed by the same player. In that case, a dark shade is used. In any given turn, if a player claims light-colored letters from an opponent, this removes the aegis of any side-adjacent protected letters.

Demonstrating a defending letter with W.

Diagonal letters don’t count for defense, only the sides. And if a defended tile and its surrounding tiles are used by your opponent, that tile remains yours, even though it is no longer accorded special status unless you protect it again.

A player can always use tiles he or she already claimed, but gains no advantage from doing so. Tiles’ ownership shifts back and forth constantly as the game is played. Play continues until all letters have been claimed, or until both players pass their turns in the same round. Whoever has the most claimed letters at the end of the game wins.

Opening moves

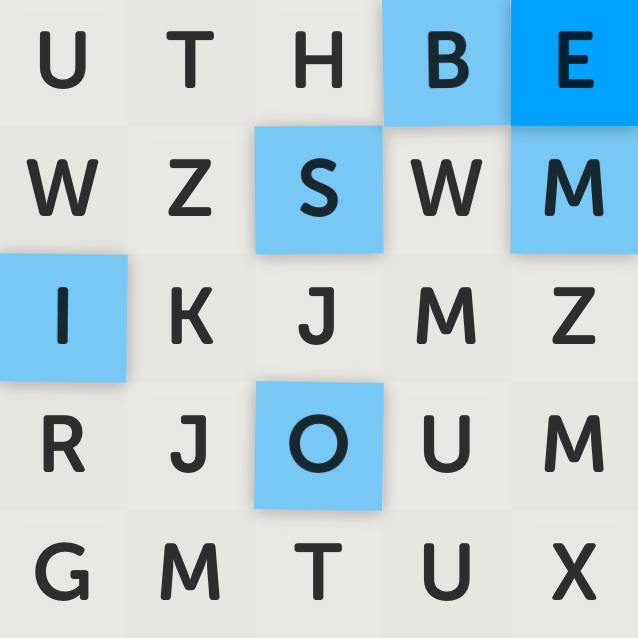

The first move in Letterpress confers a huge advantage. A well-played opening can devastate your opponent. If you’re opening the game, always defend a corner letter and make the longest word you can.

Corners are important because they’re the easiest tiles to defend and keep: only two sides need to be locked down, as opposed to three or four for all other tiles. Once a player owns a corner, it is very difficult to lose it. Opening with a defended corner provides a base from which you can expand into more defended letters, thus taking control of the board.

An opening gambit takes a corner.

Often, you won’t have much choice in which corner to take, but, if you can, defend the one with the highest-value letter — either a letter that occurs but once on the board or a vowel. Even if you can’t take a whole corner, try to take as much of one as you can. You might be able to claim it in the next round.

Beyond corner conquests, occupy as much of the board as you can in the first rounds. Each time, play as long a word as you can muster — at least 6 letters. Your opponent will surely steal many of those letters back the next turn, but don’t make it easy.

Before playing your first word, study the board carefully. See what letters lie in the corners and where the vowels and most-used consonants are. Think about some of the words that might be played in the match. Visualize the possibilities by testing out words, even for future rounds, before acting on the current turn.

Also think carefully about not just the words you can play, but how your opponent could turn them against you. Choose poorly, and even the best of openers will be for naught. For example, an opponent of mine opened with AWARES, defending a corner E. Unfortunately, he didn’t anticipate I could play UNAWARES on my turn, depriving him of all but his now-undefended corner E.

Awareness of the board, and all possible permutations of a word, is critical in Letterpress. If I play POOLED, my opponent can’t play POOL, because that’s a prefix of POOLED; but if there’s an S on the board, he can play POOLS. That’s okay, because I can strike back with LOOPS. If he plays LOOPED, I can counter with SPOOLED, and so on.

While all of that is going on, the point advantage is flipping back and forth between my opponent and myself. I call this back and forth “tick-tock.” As I’ll demonstrate later, understanding the tick-tock rhythm is essential to winning at Letterpress.

If you play following an opponent’s really great opening, you’re at a disadvantage, but not an insurmountable one. Like Microsoft in the ’90s, you want to “embrace and extend.” “Embrace” the opponent’s letters by using as many as possible, and “extend” by using unclaimed letters, preferably taking another corner as you do so.

However, the current first-mover advantage might be short lived. Developer Loren Brichter told me that he’s considering adding a “pie rule,” which would allow the second player to veto the opening move. If that happens, this section will still apply, but you’ll probably want to make less aggressive openers.

Mid game

Once the game is underway, Letterpress becomes an all-out war. Like any good general, you want to keep your troops in a tight formation. Spread your letters out willy-nilly around the board and the enemy will easily pick them off. Keep them close together to make them easier to defend.

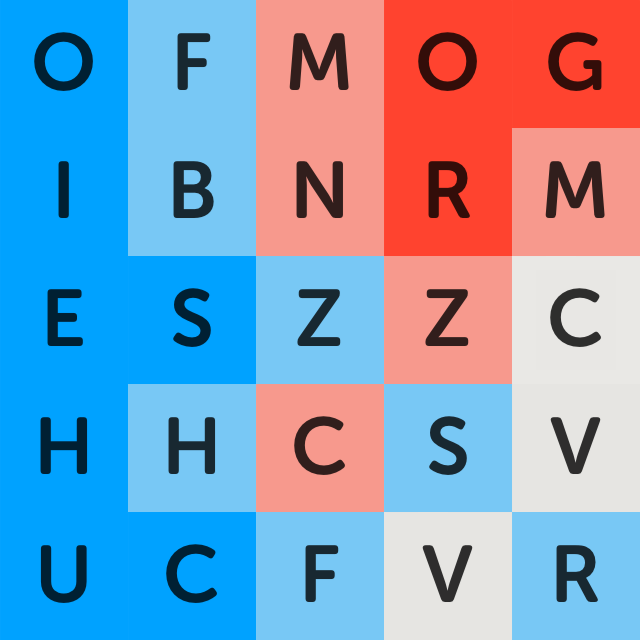

Ideally, you want to “march” across the board, claiming and defending letters line by line, building a wall as you go. If you’re able to start from a corner, you can build either horizontally or vertically — maybe both. And if your opponent gives you the opportunity to take more corners, by all means do so; just don’t spread yourself thin.

As you make your way across the board, you want to defend as many vowels as you can. According to Brichter, there are at least three vowels (excluding Y) on every board, but never more than seven. Other than ZZZ (yes, it’s legal, according to Brichter), vowel-less words are few and far between. Block them off and your opponent is cut off at the knees.

Of course, the path of glory is never an easy one. The score in a well-matched game will be a constant tick-tock between you and your opponent. For that reason, you almost never want to play a word that would leave you even or at a point disadvantage to your opponent, because he or she can then steal your letters and put you in a hole that will be hard to climb out of.

In order of priority, you want to use your opponent’s letters, unclaimed letters, and your own letters (as you get no points for reusing your own). Also, don’t fall into the trap of just stealing letters, or you’re spinning your wheels. Try to make every word a mix of stolen and fresh letters, so you can hamper your opponent as you expand. Embrace, extend, and extinguish.

Speaking of unclaimed letters, they act as something of a clock for the game. As each one is captured, the end draws closer. If you have a significant advantage, use them as fast as you can, but if you’re behind, avoid them to give yourself time to catch up. Tick, tock.

Endgame

With only a few unclaimed letters left, the end is nigh. More often than not, the decisions you make here will decide your fate.

The “tick-tock” concept becomes crucial at this point, because, in a close game, the player who ends the game usually wins. When only a handful of letters remain, ask yourself before every play, “If I do this, can my opponent finish the game?” If the answer is yes, don’t do it.

Marching across the board, the general's soldiers take tiles.

One letter I’ve often found left for last is Q. It’s a tough letter to use, because it’s seen as dependent on the letter U. But in Letterpress, U is not guaranteed to be on the board. However, if the letter Q is present, there will always be an I, according to Brichter. If you want to be a Letterpress master, learn words that use Q and I, but not U, such as QI(S) and FAQIR(S).

The best thing about Letterpress is that it lets you win in style. Some players, like Marco Arment, like to use the shortest possible word to win. I like to be clever, such as playing a high-school classmate’s own nickname against him. If you’re really good, you can “smurf” your opponent by taking every letter on the board, turning it blue.

Trying to smurf your opponent.

And if no matter what you do, you still can’t win, just remember: Profanities are legal.

Thanks to Loren Brichter for his help with this article.

Special thanks to Glenn Fleishman for his editing of this article, and for Marco Arment for allowing me to republish it on my site.